MuseumID -

Identifying museums and museum objects on the internet

- This version:

- http://museumid.net/documentation-20101206

- Latest version:

- http://museumid.net/documentation

- Author:

- Georg Hohmann (GNM Nuremberg)

- Contributor:

- Mark Fichtner (ZFMK Bonn)

Abstract

Currently there is no community agreement on unique and persistent identifiers for museum objects on the internet. The proposal at hand defines the concept of MuseumID, a free and easy solution to create and use museum object identifiers. It describes the characteristics and features of MuseumIDs and explains how they are created and established . They do not supersede but complement the currently used inventory numbers system to fit the requirements of digital data exchange and the Semantic Web.

Status of this document

This document is based on the article "Aspects of a museum object identifier for automatic data processing" [CIDOC Identifier] published in the ICOM/CIDOC Newsletter No. 01/2010. It modifies and vastly extends the proposal made in this article and converts it to a formal layout. As a work in progress, this version of the document will be constantly modified and extended.

Scope

MuseumID is supposed to be used on the Semantic Web, especially within the Resource Description Framework (RDF) and the Web Ontology Language (OWL). The text refers to several internet technologies and methods whose knowledge may be required for understanding. It does not describe technical implementations of MuseumID but provides information on how they should be created and established. This draft will be submitted to the International Council of Museums (ICOM) in a final version to become a recommendation for museum object identifiers.

Table of Contents

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Prerequisites

- 3. MuseumID

- 4. Advantages

- 5. Conclusion

- 6. Acknowledgements

- 7. References

1. Introduction

Inventory numbers are the traditional identifiers of objects in museums. Unfortunately there is no international standard or specification for inventory numbers. Nevertheless most of them share common parts. Usually they are composed of not more than three parts. The first part usually is a prefix that denotes the collection and/or the category of an object , the second part is a number that is automatically incremented with each inventoried object and finally a suffix that describes subgroups or other annotations.

Example: "Des 207 d" is an inventory number at the Germanische Nationalmuseum Nuremberg. It indicates object 207 from the collection of design ("Des") that is part of a series of objects (suffix "d"). In this case it's a plate from a specific series of dishes.Such inventory numbers are unique within one single museum, but not in a global perspective. As a result it is common to add additional information to an inventory number in catalogues or articles to clarify the global identity of the museum object, for example an acronym of the museum. Currently there is no defined standard or community agreement neither to adopt this inventory number system for the internet nor to establish unique and persistent identifiers for museum objects that can be used in a linked data environment.

1.1. URL-based identifiers as common practice

Common practice to identify museum objects on the internet is to use an Uniform Resource Locator (URL) that points to a museum's website. Usually the inventory number is used as part of that URL to identify the museum object, whereas the domain or another part of the URL gives information about the appropriate museum or collection.

Example: http://kulturarvsdata.se/NOMU/object/NM0151866However using such a scheme as a global identifier would have some drawbacks.

First, inventory numbers in use may contain special characters that could cause problems in managing and distributing them over the internet. Inventory numbers from non-European countries may contain Chinese or Cyrillic characters or show a different direction of writing (e.g. Arabic inventory numbers). Although the internet infrastructure is based on Unicode, some of these characters and language-specific features are not fully supported in URLs yet. Therefore an inventory number often has to be encoded in a way that makes it easy to use as part of an URL. The encoding solely depends on the local implementation and requirements. Completely replacing established inventory numbers with generic identifiers is also not viable because they are widely spread and are used in scientific literature on the museum objects.

Second, once published a museum has to take care of the persistency of its identifiers. As the assigned URLs are mostly part of the museum's website, it's likely that they will change due to redesign of the website.

And third, the URL setup differs from museum to museum and depends on the language of the museum. Due to the different URL policies of museums it is not possible to determine (or to standardise) whether an identifying URL uses subdomains and/or several path levels. As a result, it is not possible for scientists who are not directly involved within a museum to add additional data from research to the museum object as they don’t know the identifier of the museum object. The identifier of a museum object must be retrieved manually over the web before it can be used in a local data pool. This is one cause for low data integration in the domain of cultural heritage.

1.2. Identifiers on the Semantic Web

On the Semantic Web, identifiers play a central role. Common techniques like the Resource Description Framework (RDF) [RDF Primer] or the Web Ontology Language (OWL) [OWL Overview] use Uniform Resource Identifiers (URI) [RFC 3986] to identify and to refer to resources. These resources are not only webpages or digital files commonly referred to by Uniform Resource Locators [RFC 1738], but might also be real-world objects like cars, people or museum objects.

The URLs of a webpage on a real-world object is not the same like the URI that identifies the real-world object. Using an URL as identifier, people (and machines) are used to find something readable and processible at the location the URL points to. A W3C Interest Group Note about [Cool URIs] for the Semantic Web proposes a mechanism that enables machines to disambiguate URIs for web resources and URIs for real-world objects. But that does not work for people. Furthermore people tend to read an URI and interpret its supposed meaning. That might lead to the situation a given URI delivers data or metadata about a resource that was not expected.

Therefore it seems to be important that URIs for real-world object should be identifiers only and should not have a syntax that can be misunderstood as a pointer to a digital resource. The identifier of a real-world object should differ from a hyperlink to a resource but still be supported by the current internet infrastructure.

1.3. Requirements for identifiers of museum objects

The above considerations lead to the following requirements for identifiers of museum objects that fulfil the demands of the internet infrastructure and the museum community.

A suitable identifier system for museum objects has to take these considerations into account by being applicable in automatic data processing and information aggregation. They must have properly defined syntax and semantics and consist of generic components. The scheme has to assure the persistency of identifiers even if the website of the responsible museum changes. They have to be automatically creatable and have to be easy processible. They must assure globally uniqueness due to their construction method and should preserve existing identifiers such as inventory numbers.

2. Prerequisites

MuseumID is based on existing, widely- spread and commonly used techniques. In the following paragraph, these techniques are described briefly.

2.1. Uniform resource name

URNs are described in-depth in [RFC 1737] and [RFC 2141]. The latter describes URNs as intended to serve as persistent, location-independent, resource identifiers. The World Wide Web Consortium (W3C) defines the URN as a subtype of the URI [URI Clarification]. Another subtype of the URI is the URL. In contrast to the URL which specifies the storage location of a resource, the URN is the name of a resource. This can be compared to a person’s name (URN) and his/her address (URL). If a person relocates, the address will no longer be a valid contact point for that person and might now address another person. However the name of a person stays the same, no matter where she/he is. In short, it can be said that URNs are used for identification, whereas URLs are used for locating or finding resources. So, an URN has the advantage of making no assumption on where a resource is located and will still be valid if the resource itself ceases to exist or becomes unavailable.

An URN consists of three parts, separated by colons: the prefix "urn", the Namespace Identifier (NID) and the Namespace Specific String (NSS). The NID determines the scope and the structure of the NID. For example the International Standard Book Number (ISBN) can be expressed as URN using the NID "isbn" [RFC 3187]. Until now there is no specific namespace for the identification of museum objects. [URN Namespaces]

Example: The ISBN URN of the German edition of Goethe's "Faust" is "urn:isbn:3150000017".2.2. Universally Unique Identifier

Universally Unique Identifier (UUID) [ISO 9834-8] is a standardised definition of an unique identifier to be used in a network environment. An UUID is a 128-bit number in 32 hexadecimal digits, consisting of five groups separated by hyphens. Characters at specific positions in this number define which method was used to create it. Currently there are five versions of UUIDs.

Version 1 describes the creation of an UUID using the current timestamp and the MAC-address of the concerned computer. Version 2 is a more secure version that prevents recovering the timestamp and the MAC-address from a given UUID. Version 4 creates an UUID using random numbers only. Version 3 and 5 explain a method on how to create an UUID using the hash algorithms MD5 (Version 3) and SHA-1 (Version 5) based on a namespace (a UUID itself) and a name (an arbitrary string) as input values.

Version 5 is crucial for this proposal. According to [RFC4122], two UUID V5 generated from two different names in the same namespace are always different. If two UUIDs V5 are equal, then they must have been generated from the same name in the same namespace. To create an UUID V5, both input values are represented as a continuous byte-sequence which is hashed using the SHA-1 algorithm. This hash is allocated to the parts of the UUID that are not reserved for special values.

Example: The UUID of the DNS namespace is defined by [RFC4122] as "6ba7b810-9dad-11d1-80b4-00c04fd430c8". The resulting UUID V5 of this namespace and the name "example.org" is always "aad03681-8b63-5304-89e0-8ca8f49461b5".3. MuseumID

The concept of MuseumID consists of two components, the Museum Namespace (MNS) and the Museum Object Identifier (MOI). The MNS is an UUID V5 which serves as the unique namespace of a museum. This namespace is used for the creation of a MOI, which is also an UUID V5. The process of creating a MNS and a MOI is explained in the following chapters.

3.1. Museum Namespace

To create a Museum Namespace (MNS) first the Base Domain Name (BDN) of a museum has to be determined. A BDN is a fully-qualified domain name (FQDN) in lower case letters without a specific hostname or subdomain. It consists of the top-level-domain and one or more subdomains. A museum might have registered two or more domains and several subdomains. The domain in question is the domain that is primarily and mainly used by the museum to communicate with the public. Most likely this domain serves the museum's main website.

Example: The Louvre-Museum operates several domains like "cartelen.louvre.fr", "monguide.louvre.fr" or "www.louvre.fr". The correlate BDN for the Louvre-Museum is "louvre.fr".The MNS is an UUID V5 created using the DNS Namespace UUID and the BDN of a museum. The DNS Namespace UUID is predefined in [RFC4122] Appendix C as "6ba7b810-9dad-11d1-80b4-00c04fd430c8". To disambiguate it from other UUIDs created in different contexts and for different purposes a MNS should be represented as a URN using the NSS "mns".

Example: Using the DNS namespace UUID "6ba7b810-9dad-11d1-80b4-00c04fd430c8", the resulting UUID V5 for the BDN "louvre.fr." is "4c408e6d-610a-50fc-b5da-69520ecf9956". So the MNS of the Louvre is "4c408e6d-610a-50fc-b5da-69520ecf9956". The corresponding URN is "urn:mns:4c408e6d-610a-50fc-b5da-69520ecf9956".3.2. Museum Object Identifier

Once a MNS for a specific museum is determined, a Museum Object Identifier (MOI) can be created based on this namespace and an inventory number that has already been assigned to an object of the specific museum.

Again, a MOI is an UUID V5 based on the MNS and an inventory number. The original inventory number of an object should be used as is, case-sensitive, with all special characters, punctuation and whitespace, since UUID V5 supports Unicode.

The resulting UUID is the MOI. To disambiguate it from other UUIDs created in different contexts and for different purpose a MNS should be represented as an URN using the NSS "moi".

Example: Using the DNS namespace UUID, the resulting UUID V5 for the BDN "louvre.fr." is " 4c408e6d-610a-50fc-b5da-69520ecf9956". The inventory number of the 'Mona Lisa' is "779". Using both values to create a UUID V5, the result is "47b8b64d-8e83-564e-8b87-98803e0c5a49". So the MOI of the painting called 'Mona Lisa' in the Louvre is "47b8b64d-8e83-564e-8b87-98803e0c5a49". The corresponding URN is "urn:moi:47b8b64d-8e83-564e-8b87-98803e0c5a49".3.3. Resolving

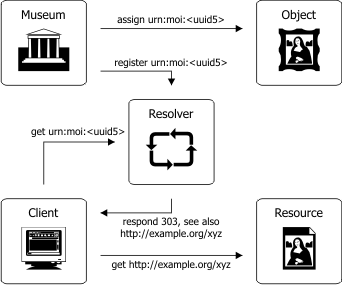

Fig. 1: MuseumID Resolver

The representation of a MuseumID as URN has the advantage of making no assumption of where a resource is. The URN will still be valid if the resource itself ceases to exist or becomes unavailable. However unlike URLs URNs are not automatically resolved by the DNS. This underpins the purpose of MuseumID to solely identify a museum object and not to support any assumption where to find metadata about it.

The connection between the MuseumID and resources that hold information about the museum or museum object can be established by a resolver. A MuseumID resolver is a web-based service that processes a given MuseumID and gives back information on the object or museum that is identified by a MuseumID. A good example of a resolver in use is the one at the German National Library [EPICUR]. Additionally they provide a plug-in for all common browsers that enables them to deal with URN like people are used to deal with URLs. This plug-in can be easily adopted for resolving MuseumIDs and may become a core part of next generation browsers.

A resolver may forward to a resource directly or give back a list of possible resources. In both cases the resolver has to distinguish exactly between the real-world-object a MuseumID identifies and a resource with data about this object. Therefore it has to implement a HTTP-code 303 ("see also") redirect as proposed by [Cool URIs]. (Fig. 1)

4. Advantages

MuseumID fulfils the requirements for identifiers of museum objects stated above and additionally has some advantages over common URL-based identifiers.

The uniqueness of the namespace of a museum is assured by the existing and established global DNS service. No new global registration service is needed. As most museums already have a domain and a website no extra efforts or costs are made. Even museums without a website can use MOI by registering a domain. As MuseumIDs are UUIDs, they only contain ASCII characters and Arabic numbers. This guarantees ease of use in technical environments. Furthermore they don't contain any human readable part in order to prevent misunderstanding or misinterpretation by people. The process of generating and managing MuseumIDs can be fully automated. Algorithms and implementations in many programming languages for these tasks are available and easy to use. MuseumIDs MuseumIDs do not replace already established inventory number systems of museums. Instead they complement these systems with a component that makes them suitable for the semantic web challenge. Because they are based on already existing data in a museum, MuseumIDs can always be generated again if needed.

Another advantage is that a MuseumID can also be generated by a third party. Inventory numbers are the primary tool in scientific discourse to refer to a specific object. So in every catalogue, book, website or data resource the inventory number of a object is published. Everyone how knows the primary domain name of a museum (louvre.fr) and the inventory number (779) of an object (Mona Lisa) can create and/or use a specific MuseumID (urn:mid:47b8b64d-8e83-564e-8b87-98803e0c5a49). This is also possible if the museum itself doesn't have any website or data service at all.

5. Conclusion

Using MuseumID the semantic web community has a reliable identifier system which could be easily adopted in existing systems without the need for the museums to build a technological infrastructure first. Such a system enables the automated aggregation of information which is a major step forward for museum object documentation in the digital age.

6. Acknowledgements

We wish to thank everyone who reviews the drafts of this document. This work was supported by the Department of Cultural Informatics of the Germanische Nationalmuseum Nuremberg, the Working Group Transdisciplinary Approaches to documentation of ICOM/CIDOC and the German Research Foundation (Project WissKI).

7. References

- [CIDOC Identifier]

- Hohmann, G. (2010): Aspects of a museum object identifier for automatic data processing. In: ICOM/CIDOC Newsletter No. 01/2010, p. 17-21. <http://cidoc.icom.museum/newsletter_01_2010.pdf>

- [Cool URIs]

- Sauermann, L.; Cyganiak, R. (2008): Cool URIs for the Semantic Web. W3C Interest Group Note 03 December 2008. <http://www.w3.org/TR/cooluris/>

- [EPICUR]

- Schroeder, K.; Slotta, A.; Roth, A. (2006): EPICUR-Resolver. Technische und Anwenderdokumentation der Dienstleistungen EPICUR-Resolvers zur Auflösung von Uniform-Resource-Names (URN). Version 1.1. <http://www.persistent-identifier.de/?link=6401>

- [ISO 9834-8]

- Procedures for the operation of OSI Registration Authorities: Generation and registration of Universally Unique Identifiers (UUIDs) and their use as ASN.1 Object Identifier components. ISO/IEC 9834-8:2008.

- [OWL Overview]

- W3C OWL Working Group (2009): OWL 2 Web Ontology Language Document Overview. W3C Recommendation 27 October 2009. <http://www.w3.org/TR/owl2-overview/>

- [RDF Primer]

- Manola, Frank; Miller, Eric (2004): RDF Primer. W3C Recommendation 10 February 2004. <http://www.w3.org/TR/rdf-primer/>

- [RFC 1737]

- Masinter, L. (1994): Functional Requirements for Uniform Resource Names. IETF RFC1737. <http://tools.ietf.org/rfc/rfc1737.txt>

- [RFC 1738]

- Berners-Lee, T.; Masinter, L.; McCahill, M. (1994): Uniform Resource Locators (URL). IETF RFC1738. <http://tools.ietf.org/rfc/rfc1738.txt>

- [RFC 2141]

- Moats, R. (1997): URN Syntax. IETF RFC2141. <http://tools.ietf.org/rfc/rfc2141.txt>

- [RFC 3187]

- Hakala, J.; Walravens, H. (2001): Using International Standard Book Numbers as Uniform Resource Names. IETF RFC3187. <http://tools.ietf.org/rfc/rfc3187.txt>

- [RFC 3986]

- Fielding, R.; Masinter, L. (2005): Uniform Resource Identifier (URI): Generic Syntax. IETF RFC3986. <http://www.ietf.org/rfc/rfc3986.txt>

- [RFC 4122]

- Leach, P.; Mealling, M; Salz, R. (2005): A Universally Unique IDentifier (UUID) URN Namespace. IETF RFC4122. <http://tools.ietf.org/rfc/rfc4122.txt>

- [URI Clarification]

- W3C URI Planning Interest Group (2001): URIs, URLs, and URNs: Clarifications and Recommendations 1.0. Report from the joint W3C/IETF URI Planning Interest Group. W3C Note 21 September 2001. <http://www.w3.org/TR/uri-clarification/>

- [URN Namespaces]

- IANA List of Uniform Resource Names Namespaces. <http://www.iana.org/assignments/urn-namespaces/urn-namespaces.xml>